This site contains affiliate links, meaning that we earn a small commission for purchases made through our site. We only recommend products we personally use, love, or have thoroughly vetted.

- A List of Advice and Resources that Helped Me in the Weeks and Months After Losing a Child

- Making Sense of Loss

- Surviving the Days and Weeks After Loss

- 1. Find a meaningful symbol to remember your child.

- 2. Read the cards and the notes when they serve you.

- 3. Discard or donate the stuff that well-intentioned people will send, without any guilt.

- 4. Don’t feel like you have to rush to make decisions.

- 5. People will want to help — let a few folks you trust help to make that possible.

- 6. Choose what hard things you want to take on and what you want to delegate, and hold the tasks you want for yourself.

- Making Your Way Through the Months Ahead

- 1. Talk about your child without apology.

- 2. Give yourself grace if seemingly small things feel impossible.

- 3. Nothing you choose to do now needs to be permanent.

- 4. Watch for times that might be hard or triggering, particularly on social media.

- 5. Find a therapist if it’s within your means, or seek out a support group you feel an affinity with.

- The House that Grief Built

- Resource Links

A List of Advice and Resources that Helped Me in the Weeks and Months After Losing a Child

First, I’m deeply sorry if you have a reason to be reading this essay. Whether you’ve lost a child or are Googling for ways to support a friend or family member who has experienced loss, I know the pain, hurt, and emptiness of the days, weeks, and months after a child dies. My second-born son died just shy of three months old in 2021.

I’ve sent long emails with some version of all of these suggestions more times than I care to count, often at the request of a friend who is looking for suggestions for another friend, cousin, sister, or colleague who experienced the unthinkable.

While I know intellectually that losing a child puts us in a terrible statistical minority, the word ‘rare’ hits differently once you’re wading through grief when a rare event happens to you.

I’m grateful for the support I’ve found in grief communities, with other loss parents with whom I’ve been connected, and kind strangers on the internet who have written other articles like this. We just passed the milestone that would have been our son’s first birthday. As my gift back to this community — that unfortunately grows daily — here’s my assortment of things that have helped me frame my grief and navigate the past year.

Making Sense of Loss

The emptiness won’t make sense. The healing isn’t the linear ‘stages of grief’ people like to talk about; it’s messy and convoluted with good days and bad days.

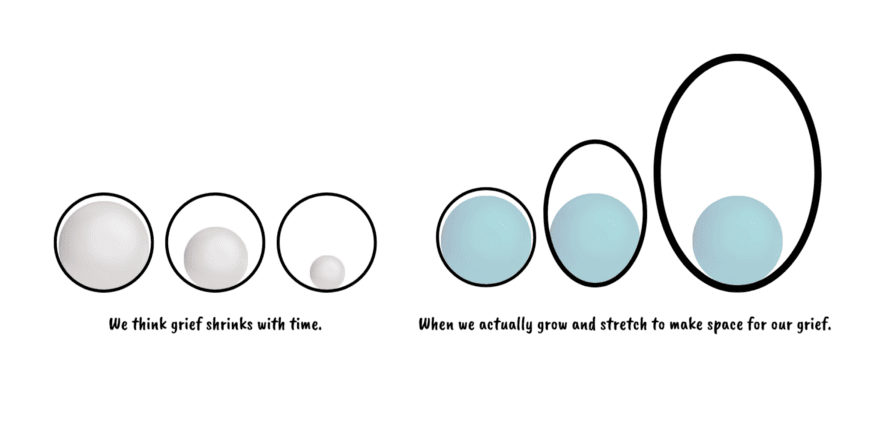

My favorite visual metaphor about grief centers on the ways the grief doesn’t shrink over time, but you find ways to grow and expand the space it occupies in your life. People think that you stay somewhat constant and stay the same size, and the ball of grief shrinks and becomes less present, but really the ball of grief and loss stays the same and you grow to create more space around it.

We know from research that the traumatic loss of a loved one is like experiencing a traumatic brain injury. Losing a child, you mourn for a life and memories that will never be, which makes finding a means of remembrance and celebration hard. Your life gets divided into before and after of your loss.

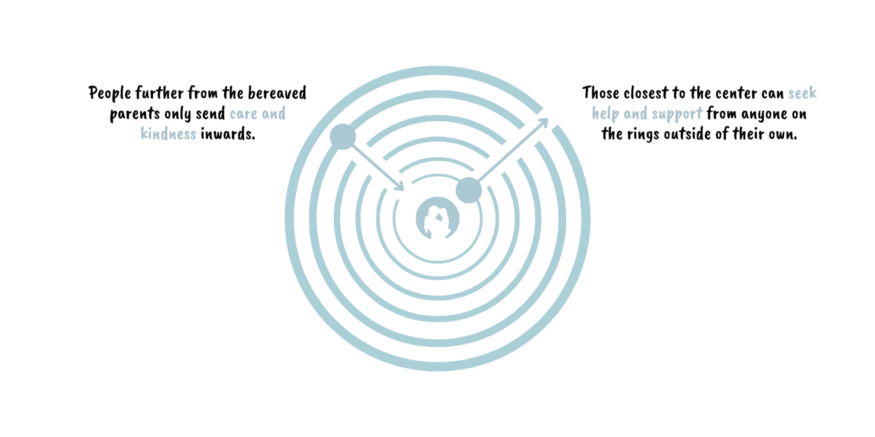

If you are someone who knows and is looking for ways to support new loss parents, please read about Ring Theory. I found it to be a really helpful organizing framework in thinking through how you can best support, and not create added burdens, for those who are grieving.

Surviving the Days and Weeks After Loss

A list, in no particular order of things that helped us and advice I was grateful to hear in the immediate days and weeks after our son died.

1. Find a meaningful symbol to remember your child.

For us, my parents had a star named for our son effective the date that he died, and so now we have a bit of a star obsession around our house. An unexpected benefit is that it’s made the mental load of decision-making around big days a bit easier.

For the day that would have been his first birthday, we had star decorations, luminaries, and balloons around the house and our toddler covered the cake with star sprinkles (and Legos, for good measure). I personally prefer a more abstract symbol over the more literal remembrances of death, which often have religious connotations that don’t mean as much to me.

I know other loss mamas who have adopted a dragonfly, a butterfly, or even a number (like the time on the clock at the moment their child passed) and find meaning when they see those little things around their world.

2. Read the cards and the notes when they serve you.

We received so many kind and wonderful notes and cards expressing sympathy for our loss. I actually didn’t open more than 100 of them for months (though I did make a point of reading the return address on each one), tucking them into a bag in our son’s closet knowing I’d get to them eventually.

There was something about the sentiment in sympathy cards (particularly those around the loss of a child) that centered on what a traumatic loss this must be for us — and I didn’t need a reminder of that heaviness I carried every day.

3. Discard or donate the stuff that well-intentioned people will send, without any guilt.

I got random care packages from different people and foundations, some of which I found borderline offensive (very religious in one case, showing that they so clearly didn’t know me well) and others that weren’t useful for me (a grief journal I had zero interest in using).

I let some of those things sit around my house for longer than I needed to. I was grateful to have people thinking of us and wanting to help, but you’ll have enough to sift through particularly if you have a nursery or child’s room full of things that may take months or longer to find the emotional space to handle.

4. Don’t feel like you have to rush to make decisions.

There are very few things that have to be done quickly as you sort out what life ‘after’ looks like. The exceptions are the things that related to the ephemeral nature of the body, like handprints and footprints and a burial if you not cremating.

We choose cremation, so there wasn’t a rush to decide on a vessel for our son to rest in or a resting place. Part of choosing cremation was so that we could take him with us if we moved rather than having a permanent burial plot near our current home. Take the time you need.

5. People will want to help — let a few folks you trust help to make that possible.

That includes saying yes to help with basic needs (like a meal train for food) and the urge folks have to send flowers / make donations in remembrance after a child passes.

My house looked like a greenhouse for a week after our son died. Over time, we aligned on a cause and directed the resources to something less ephemeral, and we had some help from friends with setting up a donation page with a nonprofit that felt meaningful to use.

You don’t need a dedicated page or fund, though — pick an organization that means something to you, and just ask that if friends and family want to remember your child, they consider a contribution to that organization. We picked something small and local to DC (PACE Moms) since the contributions would have a bigger impact on a smaller organization.

6. Choose what hard things you want to take on and what you want to delegate, and hold the tasks you want for yourself.

Friends offered to come help clean out our son’s dresser or room, and those were things that I felt were mine to do.

If you had a stillbirth or miscarriage, you may not have had a nursery set up yet, so that’s a different situation, but people are often just looking for ways to help.

Two of the best suggestions I got for ways to accept help were to say yes to pet help (like walking our dog) so that there’s one less thing to worry about, and post office/return errands (including some that were particularly hard, like sending back Christmas jammies or Halloween costume things I had ordered for him but would never get to use).

Making Your Way Through the Months Ahead

After the first six to eight weeks, the notes and sympathies slowed down. Because of the pandemic, many people never met our son (or even saw me pregnant), and when we would see friends for the first time in person, they wouldn’t even make mention of him, which was hard

1. Talk about your child without apology.

We talk about our son every day — among our family, with our firstborn, and when something sparks a memory or connection back to him. We say his name and have photos around the house of him (since he was with us for a few months).

I think it surprises some people how casually I can bring up his name or make mention of him, but there isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t think of him and miss him deeply. I don’t let myself get mired in others’ discomfort when I talk about him (though I do think it’s worth being forgiving when folks don’t know what to say in response).

2. Give yourself grace if seemingly small things feel impossible.

I still have a couple of things related to remembrances that I wanted to do that should take very little time…but somehow feel impossible every time I start them. I’ve come to accept that there will be a point when I have the mental space to tackle them, and it’s okay to wait.

3. Nothing you choose to do now needs to be permanent.

This will matter more as they approach annual celebrations, like a due date, birthday, first anniversary of the loss, or the holidays, but I felt so. much. pressure. around finding the ‘right’ thing to do to remember my son as each of those firsts arrived.

My grief group and therapist were so kind around tempering that perfectionism and functionally reminding me that traditions can evolve and change over time. Sometimes all you can do is get through the firsts. Just surviving is okay — the world may celebrate the resilience of many loss parents, but I promise we all have moments when gravity just feels stronger and it’s all you can do to get off the couch.

4. Watch for times that might be hard or triggering, particularly on social media.

For example, October is infant and pregnancy loss awareness month. This month is well-intentioned and a great time to connect with other loss parents, but for us it was the month immediately after our son died, and it was just a constant reminder of loss.

It also coincided with the time when I had my content misrepresented by antivaccine activists, resulting in a lot of targeting and harassment that tuned me out of social media for some time (which was unfortunate, as many friends sent very kind notes, and other loss parents reached out).

5. Find a therapist if it’s within your means, or seek out a support group you feel an affinity with.

This may take some trial and error, and I recognize that mental health services are expensive and out of reach for many (unfortunately).

Be selfish with your time — you don’t have to stay in a group (or even a single meeting) that isn’t serving you. Many support communities blend together miscarriage, pregnancy loss, stillbirth, miscarriage, and infant loss into a group of shared experiences, which can feel isolating or alienating early on.

With time, I’ve been able to understand the ways our collective experiences and losses are more similar than different (mourning a person who we barely got to know and the memories we won’t have), but I’ve found it particularly helpful to have a dedicated group therapy crew of other women who have lost a child.

Even in our group, each experience is different — the aftermath of loss for someone who loses their firstborn and arrives home to an empty house, compared to us, who had to explain our son’s death to our two-year-old, are divergent.

The House that Grief Built

Looking through old emails, I found a letter that my mom and dad had received from a cousin a few months after our son died. She’s experienced her own losses, and a passage in her note rings more true now than it did in the months immediately after his death:

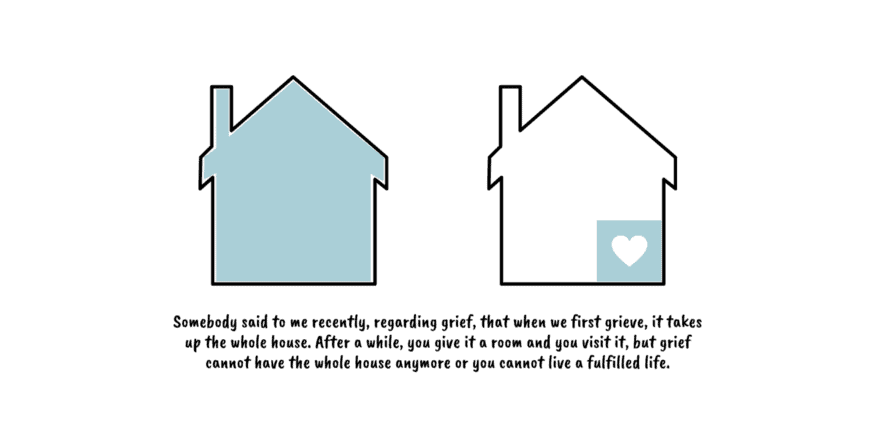

“Somebody said to me recently, regarding grief, that when we first grieve, it takes up the whole house. After a while, you give it a room and you visit it, but grief cannot have the whole house anymore or you cannot live a fulfilled life.

And as I age, I visit that room which has a lot more people than it did when I was young. The shards of grief can still pierce deeply, but have taught me a lot about suffering and the human spirit.”

These are words, reading, and experiences that are sticky for me, more than nine months after our son’s passing.

Our experience won’t be the same as every other loss parent, but the world has shown me just how many people end up joining this club that no one wants to be a part of — and the more we talk about and share the things that helped, the more we can find small ways to make that transition to this new phase of life a little bit gentler for others.

If you need urgent help, you can connect with a Crisis Counselor by texting HOME to 741741. Or you can call Postpartum Support International at 1–800–944–4773.

Resource Links

For those in the DMV: DC Pregnancy Loss and Infant Death Support Group and the Wendt Center for Loss and Healing

To find groups in other places: compassionatefriends.org (Compassionate Friends was widely recommended but didn’t end up being the right space for me personally)

Loss parents who speak about their experiences with refreshing candor: Jordan Peterson, Katie Jameson, Brittani Boren Leach, and Tom Zuba // A New Way to Do Grief

Organizations: Good Mourning Podcast, The Worst Girl Gang Ever

An even longer list, sourced from a handout from MotherNation: Grieve Out Loud, National Share, Return to Zero: H.O.P.E., Star Legacy Foundation, Pregnancy Loss and Infant Death Alliance , Pregnancy and Infant Loss Support Center, The Compassionate Friends