Grief is hard subject to talk about because it makes everyone uncomfortable, sometimes including the griever. Some people just don’t want to talk about things that are making them sad; these people are likely introverts, or at least, impressive compartmentalizers who place their pain somewhere inside and don’t discuss it externally.

But as listeners, we shy away from the conversation even more than some grievers do. When someone mentions a grief they’re experiencing, we tend to offer sympathy and then change the subject.

We need to stop doing that. We need to talk about grief because we need to learn how to talk about grief. We need to learn how to judge when someone wants to discuss their loss or trauma, and when to step back and let them have a break from discussing it. We need to learn how to be better support people. And when it’s our turn, we need to learn hour to let ourselves grieve.

We Don’t Move On From Grief; We Move Forward

This Ted Talk has been blowing up my social media feeds recently. In it, writer and podcaster Nora McInerny encourages viewers to shift how they talk about grief.

“A grieving person is going to laugh again and smile again,” she says. And it’s true. They will.

They’re going to move forward. But that doesn’t mean that they’ve moved on.

Nora McInerny

The goal of this talk, while being simultaneously gut-wrenching and hilarious, is to shift the ways we discuss grief. Recognizing the we change from our experiences of grief and understanding that it’s okay to move forward with our own lives removes some of the guilt grievers feel for their moments of happiness.

At the same time, understanding that grievers are not expected to move on helps support people feel more comfortable talking about grief. If we don’t expect people to move on, we can listen to their stories of someone they lost and we can tell our own. We can say that person’s name. We can acknowledge that person’s life days, weeks, months, and years later.

By acknowledging that people simply move forward, we acknowledge both their lived experience and the life (if it’s a life) they’re grieving.

And it’s essential that we learn to acknowledge that people more “forward,” not “on,” so we can be better support people.

Why?

Because grieving is not a solo act. It’s a communal sport.

Grieving is a Communal Sport

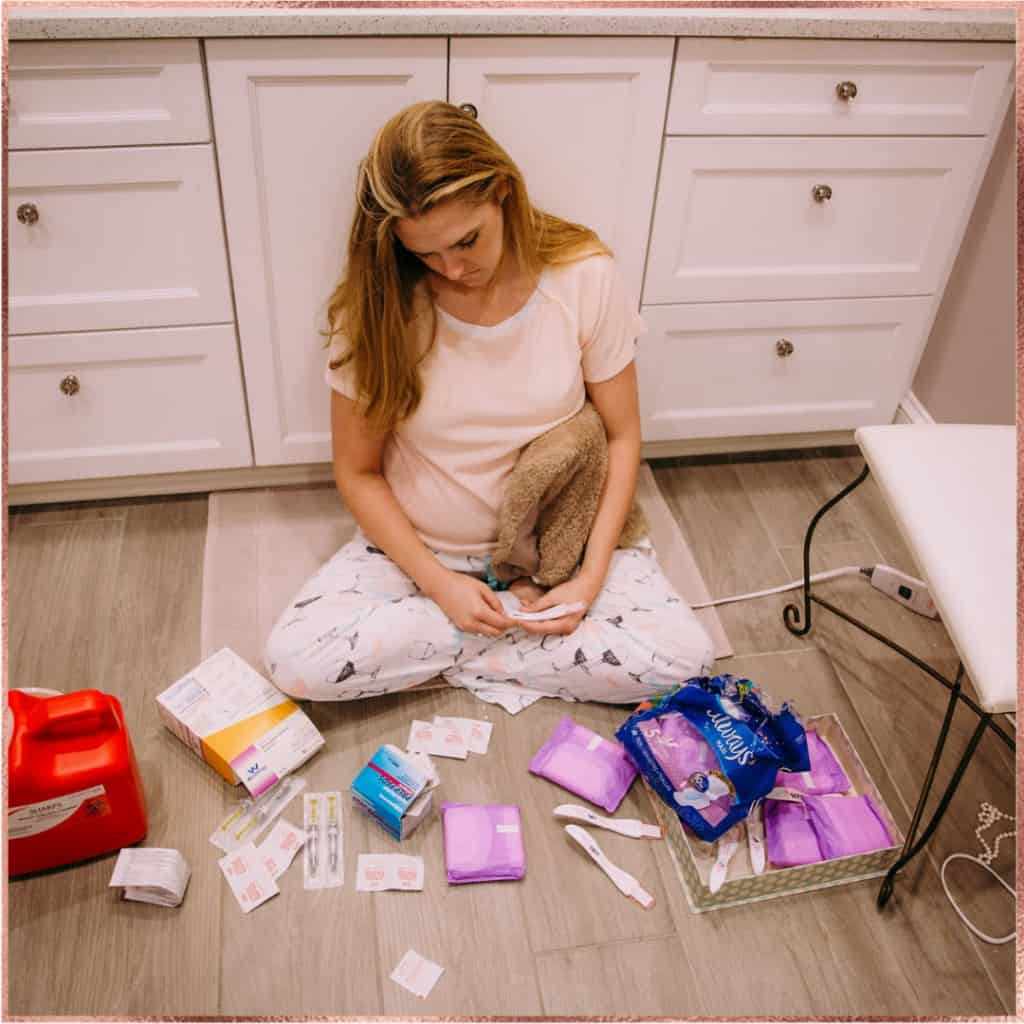

In the years that I was dealing with recurrent miscarriage, I needed people to ask about my babies, acknowledge the many times I’d been pregnant, recognize me as a mother. Very few did, and yet I’m one of the lucky ones in that way. Many recurrent pregnancy loss moms have no one to give them that validation; I at least had some.

Grieving is a communal sport–it’s arduous, painful, time consuming, requires strenuous practice that makes you sick to your stomach, leaving your entire body achy and spent. For most people, it requires a solid team to have any chance of coming out the other side of it with the closest thing you can get to a win. That is, to be able to move forward.

After I lost my first my first pregnancy, people worried and checked in on me for about a week. But their worlds kept turning, while mine either stood still or revolved solely around my grief. The concern, though, seemed to diminish with each loss; fewer people checked in, and they did it less often. I don’t know if they thought I was getting better at handling it (which, honestly, I was), or if their discomfort just became too great.

After all, what do you say to someone when, “You can always try again” and “I’m sure it’ll go differently next time” clearly don’t work anymore.

Side note: Please don’t say those things, even the first time.

When Grievers Say “I’m Fine,” Don’t Believe Them

After the first week of check-ins from friends and family, a silence began to set in. Much of the silence on the subject was self-imposed; people would ask how I was doing, and noticing the generic nature of the question, I would assume they wanted a generic answer.

“I’m fine,” I’d say.

But of course, I wasn’t fine.

And I’m usually not so fine, either. Let’s stop saying things that aren’t true.

Glennon Doyle

Luckily, I’m surrounded by some people with really high levels of emotional intelligence.

Those wonderful people would reply. “No, really, how are you?”

Then I knew I could talk.

But most people let “I’m fine” be the end of the conversation, moving on to subjects that didn’t risk jumping into uncomfortable territory. Others didn’t want to remind me of my grief, which, by the way, was constant.

When there’s no forgetting one’s grief, you need not fear reminding them of it.

I like to think people kept their questions generic because they didn’t want me to be “reminded,” and not because of their own discomfort inviting me to talk about my grief.

Either way, I didn’t want to make them uncomfortable either, so I would turn the silence into an acceptable cycle. I responded in a way that reassured my conversant that we didn’t have to talk about this terrible thing that kept happening over and over again.

I’m ashamed that I perpetuated this cycle. We must break this cycle.

Invite People to Be Authentic In Their Grief

One night, husband and I went to dinner with some of our best friends. We had both had a lot of awfulness happening; I had just lost my third pregnancy, and the husband of our friend couple had recently (and suddenly) lost his mom.

They were already at the restaurant when we arrived, and the guys greeted each other and went to get drinks at the bar, leaving two very close girlfriends to chat alone.

My friend, a delight in the emotional IQ (and every other) department, spared nothing. The second we laid eyes on each other, she leapt from her seat, ran to me, took me by the arms, looked me straight in the eye, and said the best words I could’ve imagined.

My God, this is all so shitty. Talk to me.

Thank God for her.

I talked, she listened. She commisserated without trying to pretend she understood my specific experience. She didn’t try to diminish it in any way.

In short, she was everything I love about her. I asked her about their experience and how her husband was doing, but I was careful to keep that conversation between the two of us.

Somehow, I didn’t want to “remind” him, despite understanding how flawed that logic really is.

Understand This: We Silence a Griever for our Own Comfort, Not Theirs

When we all sat down for dinner, her husband immediately started talking about our experience of miscarriage. He knew plenty about grief at that moment, and he did compare his experience to mine, but in a way that was far too generous.

He spoke of our grief as if they were the same. As much as I hate comparing different people’s grief because we all have unique experiences, I firmly believe his trumped mine. In hindsight, I believe we were the ones who should’ve been listening ears that night. But he wasn’t worried about that; he knew I needed to talk, and he listened.

I realized later that, after he listened, I didn’t ask about how he was doing dealing with his own grief. I didn’t mention his mom, or our inability to make it to the funeral because of issues surrounding miscarriage, or how his family was holding up, or ask him to tell me stories that he cherishes. I should’ve asked, but I didn’t.

So he brought it up on his own. He started talking to me about his mom, things he had coming up in life that he wished she could be there for, telling stories that allowed him to relive memories of them together.

And that’s when it happened. The moment I’m most ashamed of, but also which opened my eyes more fully to other people’s reactions to my own grief.

I changed the subject.

We Must Stop Changing the Subject

Why? Why would I have done that? At the time, I thought it was because I didn’t want him to have to feel pain by talking about his mom. But looking back on that dinner, I realize the awful truth of why I changed the subject.

I was uncomfortable.

He had allowed me to talk through my grief. His wife had allowed me the same. But when it was his turn, I silenced him because of my own discomfort. And that is unacceptable.

When someone is dealing with grief, as we all do many times in our lives, the people grieving need a team. They need people who are willing to run those laps with them, talking through the sweat, the shortness of breath, the pounding heart. We need to be those teammates for one another.

Last week, I told you the story of Jen, my guardian angel who taught me to mama, but who also never tiptoed around my grief, despite all she had going on in her life that was far more severe than anything I was going through. In the coming weeks, I’m going to tell more stories of members of the tribe of people who rallied around me during recurrent miscarriage and ran lap after lap through my grief with me.

The goal: to try to figure out what they did that was so good, and use that information to learn how we can do better.

Because we must do better.

17 thoughts on “Why We Really Need to Talk About Grief”